The market remains expensive and concentrated in a handful of mega-cap companies that all seem to share a single theme: AI. In this environment, we believe it has become more important than ever to consider a broad exposure that includes high-quality smaller companies.

Looking back at our 2023 letter Small and Focused Still Wins, we examined the Fama–French “size factor,” the forces behind recent U.S. large-cap outperformance, and the macro conditions that may shift momentum back to small caps. Rather than revisiting the macro case for small caps, this letter focuses on the mechanics of how value is created within the small-cap universe and what that means for investors trying to capture it today.

There are many commonly cited explanations of why small caps outperform: higher growth, market inefficiencies, and starting from a smaller base. These only tell part of the story. In a 2006 follow-up to their original work, Fama–French highlighted the “migration effect,” showing that a small subset (roughly 10%) of companies that grow into mid- and large-cap status explains most of the small-cap outperformance. In other words, the size factor largely comes from owning the companies that graduate upward and create lasting value.

This raises two key questions:

- Does the migration effect still exist?

- If so, are investors effectively positioned to capture it?

Does the migration effect still exist?

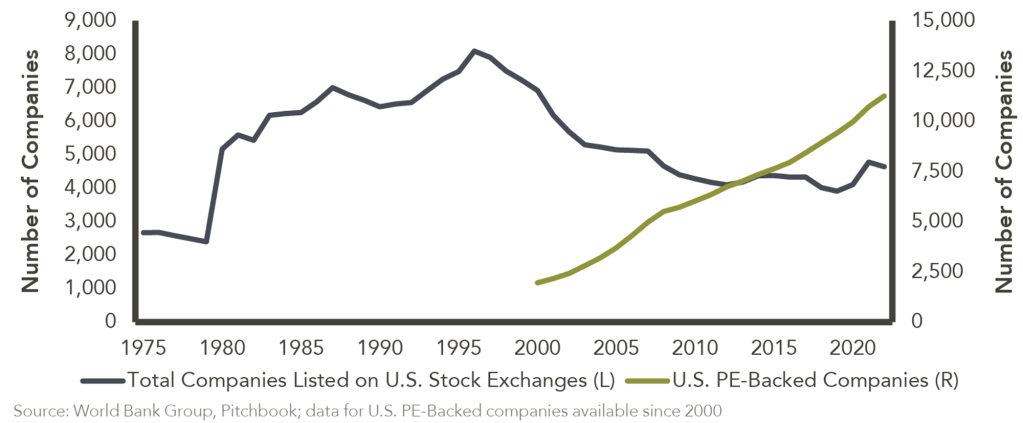

A recent narrative against investing in small caps is “the best small companies are now private,” with venture capital and private equity absorbing more of the pipeline that historically entered the public small-cap universe. It is true that the median IPO today is larger and more mature than in past decades, and the number of public companies has declined and private ones grown.

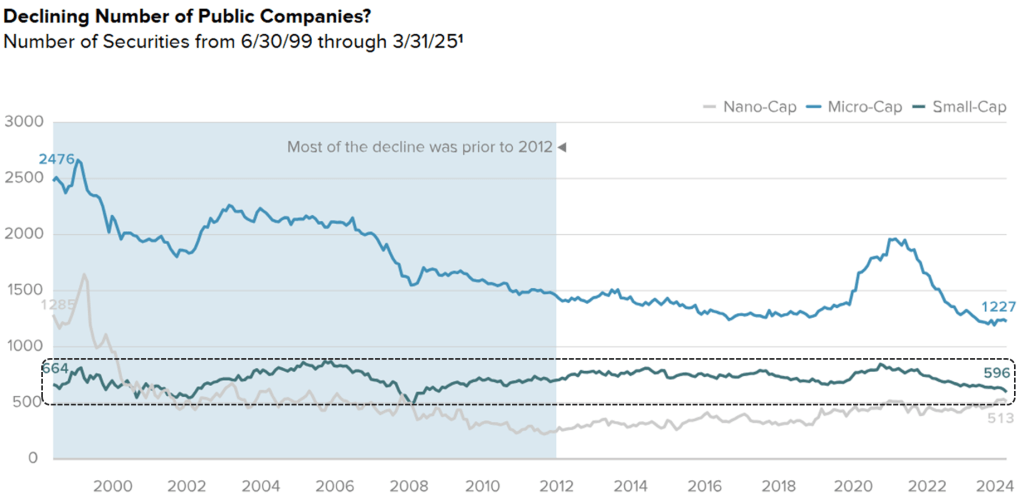

But a closer look at the data reveals a more nuanced picture. Leveraging FactSet data, Royce Investment Partners shows that the number of small public companies has actually held relatively steady over the past twenty years. The decline comes mostly from even smaller nano- and micro-caps, with a majority of the decline occurring prior to 2012. If we focus only on “small-cap” companies, the opportunity set is roughly the same.

What about the quality of this opportunity set? Over the past few decades, the share of companies in the Russell 2000 with negative earnings has risen from roughly 20% to 40%[1]. Yet, the percentage of market cap moving from the Russell 2000 (smallest 2,000 stocks) to the Russell 1000 (largest 1,000 stocks) each quarter has averaged about 2% over the last twenty years[2]. The takeaway: while the quality of the average small company has declined, opportunities remain.

This dynamic makes rigorous research and a deep understanding of holdings more critical than ever. With both the quantity (and arguably the quality) of small-cap sell-side research in decline, the market has grown less efficient, not more[3]. In this environment, active management for small caps doesn’t just make sense, it is essential.

Our findings suggest that opportunities to identify migrating small caps persist, particularly for those willing to do the work. At Richie Capital Group, our portfolio of high-quality, often overlooked businesses reflects this reality.

Are investors effectively positioned to capture the migration effect?

For a surprisingly large number of managers in the institutional investment world the answer to the above question is, “no”. Style boxes, over-diversified portfolios of 100+ names, fear of benchmark deviation, and strict market-cap limits all hinder the ability to capture the migrating small-cap effect.

Consider the standard market-cap limits: $2 billion for small-cap and $10 billion for mid-cap. When Morningstar introduced its style boxes in 1992, Exxon was the largest company at $76 billion, and those cutoffs made sense. They have not been updated to account for the ~2.3x inflation and the largest companies now being 50× bigger. Calling a $10 billion company “large” next to a ~$4 trillion Nvidia or Microsoft feels disingenuous. It seems irrational to sell a great business that remains small by today’s standards simply because it crossed an arbitrary 30-year-old market cap limit, rather than based on its future prospects.

Why do these self-imposed constraints exist in a world focused on risk-adjusted returns? Managers running 100-plus stock portfolios don’t need to invest time studying each company in their client’s portfolio, have little incentive to deviate from the benchmark, and can raise more assets with more holdings. Many allocators often prefer such strategies because they fit neatly into a “small-cap bucket” and closely track a benchmark, minimizing the chance of meaningful underperformance but also eliminating any possibility of meaningful outperformance. The result is mediocrity. With this approach, investors are better served buying a low fee ETF.

At Richie Capital Group, our core investment philosophy, our research process, and portfolio construction are all optimized to capture migrating small caps. The approach can be summarized simply: “find great opportunities early, invest, and hold as they scale”. Focusing a portfolio on the best 15-20 such names allows for diversification while also maximizing the upside from identifying opportunities early. The approach may sound simple, but executing it successfully requires discipline, experience, and the conviction to deviate from consensus.

Author: Eric Crown

[1] Sløk, T. (2023, November 17). 40% of companies in Russell 2000 have negative earnings. Apollo Academy. https://www.apolloacademy.com/40-of-companies-in-russell-2000-have-negative-earnings-2/

[2] Fang, D. (2025, April 24). Small caps vs. large caps: The cycle that’s about to turn. CFA Institute. https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2025/04/24/small-caps-vs-large-caps-the-cycle-thats-about-to-turn/

[3] This trend is primarily due to a structural economic and regulatory shift: European MiFID II rules forced investors to pay directly for research, collapsing buy-side budgets by billions and making coverage of unprofitable, less-traded small caps the first to be cut. This effect is compounded by the explosive growth of passive investing, which has dramatically reduced the market’s overall demand for active, in-depth sell-side research.

Leave a Reply